Financial Times, Daniel Dombey

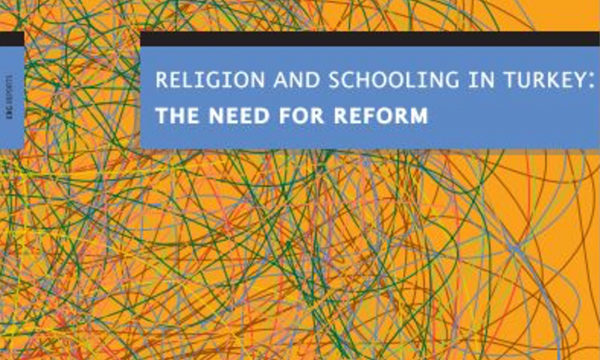

Recep Tayyip Erdogan is making his mark as Turkey’s first directly elected president barely a week after taking the oath of office. The former prime minister is already shifting Turkey away from customs acquired over the nine decades since the end of the Ottoman Empire, a period in which largely secularist elites held sway.

In the most symbolic break with the past, Mr Erdogan announced last week that he would not work out of the Cankaya Palace, the seat of the presidency since the era of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who founded the modern Turkish state. Meanwhile, Turkish newspapers report that thousands of children whose parents preferred secular institutions have been allocated places at Islamic schools.

These early moves are seen by Soli Ozel, a professor at Kadir Has University in Istanbul, as part of a broad trend in which Mr Erdogan and his Justice and Development party (AK party) are rejecting much of the country’s secularist legacy. “Their view is that the Turkish modernisation project via westernisation was ill thought out,” he said.

Mr Erdogan has set out a goal of “raising a religious generation” and pushed through legislation in 2012 that allowed children from the age of 10 to attend state religious schools.

The beginning of the first academic year under his presidency has been marked by controversy over reports that thousands of children whose families listed other schools as their first choices have instead been allocated these religious schools – the numbers of which have almost doubled since 2010, according to the Education Reform Initiative of Istanbul’s Sabanci University.

The scale of Mr Erdogan’s ambition was highlighted by one pro-government newspaper’s headline after his inauguration on August 28. The Star daily announced that the bond between the country’s leader and the people had been restored after 91 years – a reference to Ataturk’s establishment of the republic in 1923.

Mr Erdogan’s real estate plans are in line with this grandiose vision. Instead of the Cankaya Palace, which boasts 1930s features designed by an Austrian architect and supervised by Ataturk, the president plans to move to a 1,000-room complex being built in the forest outside the capital.

In a reference to past Turkish imperial traditions, Mr Erdogan says the new building combines Ottoman and Seljuk features, referring to the two leading imperial lineages of Turkey’s past.

To some, his decision is the Turkish equivalent of moving the US president out of the White House – although in a twist of irony, the new residence will be called the White Palace, the standard Turkish translation of the US president’s residence.

“Cankaya is colossal in the hearts of the people of the republic,” wrote Ertugrul Ozkok, a Turkish columnist, in a recent piece titled “Mr President, don’t leave Cankaya,” arguing that Ataturk’s palace symbolised Turkey’s victory in its 1920s war of independence from foreign foes.

But other commentators have praised the new building as the emblem of the president’s vision of a “new Turkey”, a country he says will fully empower the pious masses largely marginalised during decades of post-1923 secularist rule.

“Everyone in Ankara knew this was [Erdogan’s] dream,” Ozcan Tikit, a pro-government columnist, said of the new building, hailing the new construction as “stupendous”.

Mr Erdogan greeted his election as president last month with an inclusive speech that appealed to the “people of Turkey” rather than to ethnic or religious ties.

Nevertheless his governing style – sometimes accused of setting his pious supporters against other parts of society – has been subject to increasing international criticism.

In a pointed summary, the White House said that at a meeting at the Nato summit on Friday US President Barack Obama discussed with Mr Erdogan “the importance of building tolerant and inclusive societies and combating the scourge of anti-Semitism.”

Mr Erdogan spends much time in Istanbul, his native city. There too he is making a move loaded with symbolism, opting to no longer work from the Dolmabahce Palace, the 19th-century Versailles-style caprice where Ataturk died.

Government officials say they do not know where he is heading instead but one likely alternative is the Vahdettin Mansion on the Bosporus strait. Construction has already begun at the site which, perhaps coincidentally, is the seat of the last Ottoman Sultan.