Umay Aktaş Salman

ERG Researcher

When discussing education policies, systems and problems, teachers, students, and parents remain as the hidden subjects in most cases although they are the key components of the system. The facts and statistics alone are not enough to argue education. There lies a reality beyond data, that takes place inside the classrooms, the houses, and on the streets. Data are made of the figures which contain human stories. Our blog post series “Long Story,” discourse the education with the human stories besides the expert opinions and current statistics.

She turned her scared eyes away from her teacher’s. She was quiet; she was at a country, at a school where she cannot speak the language. She was hesitant and shaky while standing at the blackboard. She did not say a single word for two days. She kept turning her eyes away from her teacher’s when her teacher wanted to talk to her. At the end of the second day, when other students were drawing pictures, the teacher approached her and drew the picture of her house on a piece paper. Using her gestures, the teacher asked her if she could draw her own house or not. She drew the house that they had to leave. The house had a large terrace and there were two bicycles on the terrace. She also drew herself holding colorful ribbons. Next, the teacher drew her dog, and her student responded to her by drawing her cat. This was the first step that started the conversation between Teacher Gülay and her Syrian student.

It was always possible to reach every student regardless of their religion, language, and their special needs. There was always a way to reach every student as long as you want to reach them and acknowledge them.

The teacher candidates who have not yet graduated from The Faculty of Education but have been doing their teaching practicum, and those future teachers who have refugee students in their classrooms, at their schools and who have witnessed those students problems all have come together. The topic of this Teachers’ Network meeting, where the teachers share their experiences, was “I have a refugee student.” 25 teachers are telling each other the situations they have encountered in classrooms and schools, and talking about how an inclusive education is possible. In fact, they are learning from each other and spreading the solutions.

Starting the story with a different language…

Sümeyye Anıl teaches Turkish at a private language school. She tells us that she teaches Turkish using songs, karaoke, and stories. Studying and applying the method of storytelling, Anıl says, “The word ‘refugee’ means to take shelter from danger, so we take the stories as our shelter from danger. Stories connect us together.” She says when she starts a story with “once upon a time” in Arabic, Kurdish and Farsi, she catches the attention of her students at that moment. She adds the fact that by doing so, she sends the students the message, “I acknowledge and accept you and your reality,” and after that, everything goes smoothly between her and her students.

“Everyone should bring money, except for the Syrians!”

Another teacher emphasizes the fact that the refugee students should not be put on the spot. It has been told that sometimes certain behavior, despite with good intentions, might cause isolation and discrimination. Teachers start giving examples. A teacher states that one of her colleagues said, “Tomorrow, everyone has to bring money for paper; except for the Syrians.” A school administrator points out that donations for the Syrians should not be done explicitly. A teacher candidate exemplifies a situation occurred in the school he has been doing his internship by reporting that the two Syrian students are seated in the front row. An experienced teacher mentions that one of the parents of her students told the other parents that Syrian students were spreading disease to other students. She also explains what she told the parents to prevent the transmission of prejudice and to stop discrimination. She says she explained the concept of hate speech to those parents. It has also been told that there are some parents saying, “Please, do not let my child play with them [the syrian students] ,” or “They have violent tendencies since they have come from the war.”

A teacher says that a section of the social sciences textbook states how Turkey helps out the Syrian refugees and adds that attention is predominantly given to the “helping out” aspect rather than the social aspect of the situation. The teacher also says that her eyes met her Syrian student’s embarrassed eyes and made the following explanation to her class: “Ibrahim’s father works just like your fathers do.”

Inclusive education examples from the teachers

Teachers sometimes feel left alone about the methods they need to follow to handle the refugee students. However, the best methods are still suggested by those teachers. Every single method the teachers apply in their classrooms are very good examples of inclusive education.

One of those teachers is Mine Aksar, a teacher at Kazım Özalp Elementary School in Zeytinburnu. She teaches a class of 36. She has five Syrian students in addition to Afghani and East Turkistani students.

Although it is the second grade, Aksar states that there are 10 students in her class who cannot read and write. She says each of them has different needs:

They have made a multi-language dictionary

“It was quite challenging for me. I asked for the support of the other students by explaining the situation to them. ‘Your classmates want to move on to the reading-and-writing stage. In addition, we have to move on to different activities with the rest of the class.’, I said. Eventually, there was no one left who could not read and write. The Provincial National Education Directorate had a “Dictionary is freedom” project. I modified it a bit, and enlarged the concept. We made a multi-language dictionary. When we learned the word “chef,” we also learned it in Afghani, Uighur, and Arabic because assuming that those children do not exist is discrimination. When we do an activity in the classroom, those students do not participate. If one lets the situation persist the way it is, that is also discrimination. The teachers might be vulnerable in terms of competency, but I believe the teachers are more independent in the classrooms. It is our decision whether to modify, enrich, and make it more inclusive, or not.”

In addition to her efforts in the classroom, Aksar did an activity to introduce all the refugee students at the first and second grades to their peers. She saw that the students remained in their own groups due to their language barriers. For a month and a half, she did a school drama activity on the weekends where the Turkish and the refugee students came together. The school administration provided the opportunity. Her colleagues sent their students to the school drama activity, supported Aksar’s project, and even some of them participated in this project.

They overcame the language barrier with drama

The Afghani, East Turkistani, Syrian, and Turkish students overcame the language barrier with drama. Aksar explains what they did and what changed in this time period as follows:

“We thought about what kind of activities we could do with very limited vocabulary to make them realize the fact that they are indeed separately recognized and acknowledged individuals. Although I thought this project would not attract much attention, it started with 18 people and finished with 23. In the circle we started our play, each student greeted the other in their own language. For instance, we did a pantomime performance. In the performance, the students told the children’s games in history. They realized that the children’s games were similar in different countries. The students got closer; the play had a pivotal role in connecting the students. I observed the students on the weekdays during the weekend drama project. The students started to greet each other after the drama practice even though they did not speak each other’s languages. Their violent behavior decreased, and communication increased.”

Aksar points out that a teacher’s attitude affects the atmosphere at a great extent. She adds that the adults’ prejudiced behavior is sometimes reflected on the communication in the classroom. Aksar emphasizes now is the time the schools should be structured according to these principles, and the administrators and teachers should be provided opportunities to improve in this field. She adds, “The teachers should be motivated in this area with a realistic implementation.”

The next exemplary activity is from Gülay Bulut, a teacher for 21 years. She teaches at a public school in Fatih. She has a class of 28 with 2 Iranian, 1 Turkmen, and 2 Syrian, in total 4 refugee students. Her 4th graders graduated this year. She says when her Syrian student first came to her class, the student communicated by drawing pictures, and that’s how she built a connection with that student. Now the 4th grade graduate Syrian student wants to be a teacher in the future, and when the war is over, he wants to go back to his country and work there as a teacher. When he becomes a teacher, he will invite his teacher, Gülay Bulut, to his classroom. They spent the whole academic year imagining that this would come true one day. Bulut emphasizes that the teacher’s attitude toward the refugee students determines the attitude of the whole class. She is the living proof of what can change with the help of empathy and respect for the children:

“Hurrah! We have a new friend in class!”

“I do the same thing when a new student joins my class. I say, ‘Hurrah! We have a new friend in class!’ ‘Hurrah! We’re going to learn new games from her!’ In fact, the children do not discriminate. They do not see the new student as a ‘Syrian’. The parents’ attitude is directly related to the children’s and teacher’s attitude. If a teacher discriminates a child in class, the other children discriminate him or her even further. When the parents of my students asked me if we have Syrian students in the class, I talked to them about it. I explained that it does not have any significance. I told them if their children are being called the boy and girl from Adıyaman. The children have a very strong ability to conform; they understand the value of being at school, and they learn very fast. They help each other a lot. They are very well capable of establishing their friendships. I do not know at what age we start to discriminate. I had a student with autism in my class, and I did not draw any special attention to him, either. The children think that Yusuf is different, but they think this is who Yusuf is. All children are different from each other. A child might have a behavioral or an academic problem. It does not matter if a child has autism or he is from Syria. This is a natural way of thinking. The children should be able to learn this concept just like that.”

“We need support”

Bulut mentions that the teachers are caught unprepared for the refugee students. She adds the teachers need more support, and she and her colleagues need to share their experience:

“Teachers have a fossilized approach. The Ministry of National Education did a seminar on inclusive education. The timing of the seminar and the short notice for teachers did certainly not help, but the teachers still could have benefited from it more efficiently.”

“Only if the teacher provides an opportunity”

Nehir Sevimli, a Kadırga Elementary School teacher, has a multicultural class. She has 27 students in her 2nd grade class. Seven of these students are from Syria, one from Senegal, and two from Moldova. She says because she started teaching these students at the 2nd grade level, there isn’t a significant problem in terms of literacy and speaking Turkish. Sevimli shares her methods and experience as follows:

“The children do not care where they come from. They are not even aware of such a thing. For instance, one boy and two girls are older than the rest of the class. Those students’ physical development is different from the rest of the class. Despite such a difference, there is no discrimination. As long as the teacher provides a space to set the class rules altogether, there will not be such thing. This year we did a violence-free circle activity. We asked each other, ‘How do you feel today?’ We created an imagination center. I asked them, ‘What are you curious about today?’ They asked their questions to each other in groups. These activities were very nurturing. The administrators and teachers’ point of views are also very important. They do not discriminate. They do not associate a child’s situation with him/her being a refugee. The parents also cooperate.”

National goods week turned into a day introducing different cultures

One of the most effective methods that Sevimli used in her class is to change the National Goods Week into a day to introduce different cultures:

“When I asked the children what they wanted to do for the National Goods Week, some said they would bring their favorite food, and some said they would bring the most popular food of their hometowns. We all come from different places. The children from Batman brought honey, the ones from Ordu and Giresun brought tea and hazelnuts. We drew the city lines of their hometowns with colorful pencils on the map. We added the map of Africa and marked Senegal, and put the Syrian map next to it. The students marked the places that they were born in. Everyday, two or three students brought something. For instance, the child from Senegal brought rice with different spices. The Syrian students brought food that they would cook for special occasions in Syria. We tasted the food all together. I also found short videos about children’s hometown and we watched those videos to learn about those places. After the week was over, some students said, ‘Teacher, can you please turn on the videos about Muş, Trabzon, and Syria so we can watch them again?’ The children learned that dissimilarity was normal, and that was the ordinary.”

Sevimli states that visiting the Syrian students’ families made a very positive impact. She is a teacher of 17 years with a passion for professional improvement. She also took education in telling fairy tales. Sevimli adds that teachers have to be very observant about their own fields and keep an eye on the improvements and changes happening around them and in the world. She says, “Teachers’ personal efforts, time, and budgets may not be sufficient; they need to be supported by various educational opportunities and with the other teachers’ collaboration.”

How inclusive is education?

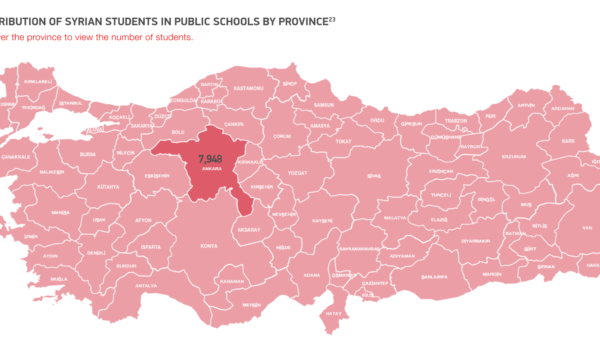

How much of the inclusive education practices are implemented in Turkey then? Is there an educational system that can meet the needs of all students regardless of their gender, ethnicity, language, religion, region, health status, and socio-economic situations? If we consider these questions from the refugee students’ perspective, we have the data mostly about Syrian students. There are 1 million 150 thousand Syrian children in Turkey between the ages of 5 and 18. The Ministry of National Education took very important steps for schooling the children. The rate of schooled children raised from 37 percent to 62.35 percent. However, 38 percent of the children still do not have access to schools. The Ministry of National Education also offers Turkish language courses, remedial courses, teacher education courses, and awareness courses. The number of students mainly from Afghanistan, Iraq and Somali is 42 thousand. That being said, the data about the refugees other than Syrians is very limited.

They have access to education, but…

Müge Ayan from Bilgi University Sociology and Educational Studies Center (SESC) emphasizes that access to education is not only limited to the physical access to schools as there are problems impeding inclusive education:

“The Syrian children are put in a position of receiving education in a language they are not competent. The language issue is a very complicated issue. By schools and NGO studies, this issue is usually reduced to teaching Turkish to the refugee children. However, it is necessary to think about the issue in the context of teaching refugee children Turkish and the representation of their mother tongues at schools. The global studies on ‘multilingualism and education’ show that the most effective outcomes come from the education systems in which children start their education in their own languages, the dominant language (in our case, Turkish) comes into play later on, and a bilingual education follows afterwards. The students can only reach the language proficiency to understand the field specific information (e.g. mathematics) in another language only if they receive education in a system mentioned above.

The education of the parents is very important

Ayan underlines the need to conduct comprehensive studies to fight against the prejudiced attitudes in order to apply inclusive education practices:

“There are prejudiced approaches toward refugee children, which have no ground in real life. This has the teacher, parent, and student dimensions. Witnessing adults’ prejudiced and discriminating behavior provokes children to bully their peers. Therefore, it is necessary to show parents and teachers that what they may know as the right behavior might actually be wrong.”

Stating that teachers’ methods, which are expressed at the experience sharing meetings, indicate the sense of belonging very clearly, Ayan emphasizes “Children feel belong to their school when they find certain aspects about their own languages and cosmologies.”

“These good examples should not remain as individual efforts”

Ayan points out that strategies that are developed by teachers are very important, yet, unfortunately, they remain as individual efforts:

“It is necessary to hear strategies that work out, to share experiences, and to spread good examples. Teacher’s Network functions as a platform to provide an environment for the activities mentioned above; this is very valuable. It is also very important that the Ministry of National Education should consider the issue from inclusive education perspective. However, since the interactive methods are not used much in the teachers’ professional development trainings, they end up with being not very efficient. Teachers leave these training sessions with no practical methods to help them to apply on classroom practice. In these trainings, the language issue needs to be discussed more deeply. There is a significant number of Syrian teachers living in Turkey. I believe teachers should be considered as valuable resources.”

Leaving problems of physical conditions of schools, overpopulated classrooms etc. aside, teachers’ experiences and stories are the evidence of what can be overcome only even by communication. It is fundamental to hear out teachers, provide opportunities, and support them in order to multiply the good examples and spread them.

* In this regard, with the cooperation of Teachers’ Network and SESC, there will be a symposium at Istanbul Bilgi University on September 22nd, 2018 to disseminate the knowledge and experience gained by NGOs and teachers.