Reuters, Dasha Afanasieva – Can Sezer

Turkey has seen a sharp rise in religious schooling under reforms that President Tayyip Erdogan casts as a defense against moral decay, but which opponents see as an unwanted drive to shape a more Islamic nation

Almost a million students are enrolled in “imam hatip” schools this year, up from just 65,000 in 2002 when Erdogan’s Islamist-rooted AK Party first came to power, he told the opening of one of the schools in Ankara last month.

The schools teach boys and girls separately, and give around 13 hours a week of Islamic instruction on top of the regular curriculum, including study of Arabic, the Koran and the life of the Prophet Mohammad.

“When there is no such thing as religious culture and moral education, serious social problems such as drug addiction and racism fill the gap,” Erdogan told a symposium on drug policy and public health earlier this year.

But in the drive to create more imam hatip places, parts of schools have been requisitioned, prompting protests from parents who want secular education for their children.

“We are against the governance of education by religious rules,” said Ilknur Birol, spokeswoman for the “Don’t Touch My School” initiative, an umbrella grouping for angry parents. “This system is not rooted in youth with a forward-looking perspective enlightened by science, but in a generation that values obedience.”

Filiz Gurlu, a parent at the Kadir Rezan Has school in Istanbul where one of two buildings was converted to imam hatip facilities, said primary students were now cramped in a single building.

“The library, laboratory, computer and music rooms were in the confiscated part, so the kids don’t have access anymore,” she said. “Some classrooms have barely enough space … This is an unplanned move, kids just can’t simply fit in.”

HAPHAZARD

The debate over education straddles a faultline in Turkish society dating back to the 1920s, when Mustafa Kemal Ataturk forged a secular republic from the ruins of an Ottoman theocracy, banishing Islam from public life, replacing Arabic with Latin script and promoting Western dress.

Erdogan, who won Turkey’s first popular presidential election in August with 52 percent of the vote, has cast himself as a champion of the rights of the pious, redressing the balance after decades of Kemalism.

“If during their education our youths become alienated from their language, history, ancestors, culture and civilization, it means there is a very serious educational problem there,” he told a national education convention on Tuesday.

Opponents say Erdogan’s style of rule, giving supremacy to what he believes is the will of the majority, means their views are ignored.

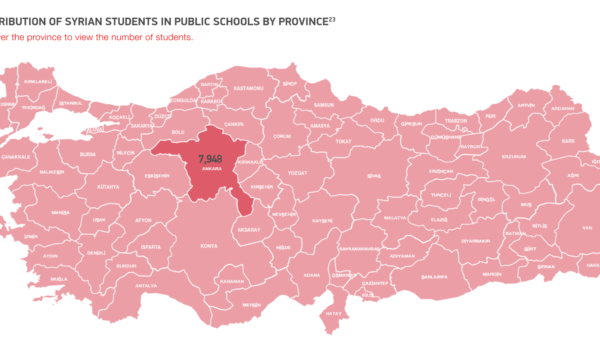

Huseyin Korkut, head of the imam hatip alumni association, said there was strong demand for imam hatip schools, but his assertion was based on surveys in just three regions, the broadly conservative Kayseri, Konya and Erzurum provinces.

He said the body had urged the government in vain to conduct a nationwide survey.

“Changes in school types were decided by local bureaucrats in a rather arbitrary manner,” said Isik Tuzun, a coordinator at the Education Reform Initiative, a think-tank at Istanbul’s Sabanci University. “(It) has definitely been rushed.”

The Education Ministry did not respond to requests for comment, but the government maintains the changes are driven by demand. Education Minister Nabi Avci said in November that demand for imam hatip places rose this school year and last.