Newsweek, Alexander Christie-Miller

When Hasan Erol and other parents learned that their children’s school would be converted to specialise in Islamic education, they hit the streets. Yeşilbahar Middle School is among five in Istanbul’s staunchly secular district of Kadıköy to have been earmarked for conversion into imam-hatips, religious schools in which 20% to one-third of hours are dedicated to Sunni Islamic study. “They want to transform this area into something else,” says Erol, whose 13-year-old son goes to the school. “They want to make it more conservative by bringing imam-hatips here.” Yeşilbahar was spared. Authorities relented in the face of protests and a petition and, for now, it remains a general middle school. There have been drawbacks, however. This year, no new students have been registered. In a meeting with officials, Erol claimed, the regional education director threatened to stop enrolling students altogether so that, in time, “they will have no parents to deal with”.

Yeşilbahar is among hundreds of schools in Turkey caught up in an education overhaul that, critics claim, is an attempt to roll back the country’s 90-year-old secular project. The government says it is responding to demand, but parents and teachers from half a dozen affected schools around Istanbul say that the conversions are being pushed through in spite of communities’ wishes, and that pupils are being shuttled from distant parts of the city to fill classes at the new religious schools. Ever since they won power in 2002, the Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its charismatic leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan have been accused by their secular opponents of trying to turn Turkey into Iran.

For a long time, Western pundits and governments rolled their eyes at this so-called secret Islamist agenda. In its early years, Erdoğan and AKP forged a reputation as reformists, passing EU-inspired legislation, and subduing Turkey’s once-meddlesome military, seemingly to create a more liberal, pluralist society. More recently, however, Erdoğan – who ascended from prime minister to president in elections in August and enjoys a level of authority comparable only to that of Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – has spoken more openly of his desire to recast the country along conservative lines. “We want to raise pious generations,” he told an assembly of AKP youth members in 2012. The party’s new catchphrase calls for a “New Turkey”.

While Erdoğan’s defenders say this means the tolerant, inclusive society that AKP pledged to build on taking power, his opponents claim the phrase connotes populist authoritarianism with conservative Sunni Islamic overtones. “The ‘New Turkey’ will not be somewhere where democracy and freedom are celebrated. It will be a place dominated by Islamic thinking,” says Dengir Mir Mehmet Fırat, an AKP co-founder and former member of its executive committee, who abandoned the party in 2011 and now accuses it of ditching its liberal principles. Education reform, he believes, is part of the AKP’s attempt to “manipulate society towards a more religious way of life”.

In recent years, a slew of government initiatives has pushed Islam deeper into Turkey’s nominally-secular education system. Examples include a plan to build mosques in 80 different state universities, and a scheme to convert one Istanbul university into a centre for Islamic learning. This month, a government-backed education council recommended extending compulsory religious classes to all primary school pupils, as well as adding an extra hour of obligatory religious classes for all high school students. That decision came in spite of a ruling in September by the European Court of Human Rights, which ordered Turkey to stop the existing one-hour-a-week compulsory religious classes for middle- and high-school pupils.

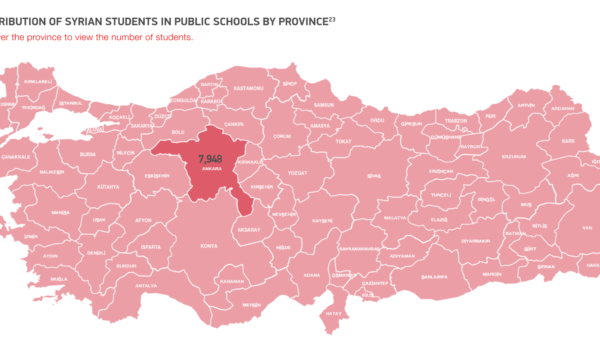

Nowhere is the spread of Islamic education seen more clearly, however, than in the steady expansion of imam-hatip schools. When AKP took power in 2002, around 65,000 pupils were enrolled in them; today, the figure is nearly one million, or 9% of all school children aged between 10 and 18. Most of this increase has occurred since 2010, when AKP legislated to transform general high schools into vocational schools, including imam-hatips. Since then, their number has increased by 90%, from 493 to 936. In 2012, it legislated to allow middle schools to also operate as imam-hatips as well, meaning children as young as 10 can now attend them.

Turkey’s education ministry says the proliferation is in response to demand. “In all of these processes, the changes that have been made are according to the needs and demands of our parents and pupils,” a spokesperson says. However, Batuhan Aydagül, director of the Education Reform Initiative at Istanbul’s Sabancı University, believes the government is driving the demand, not responding to it. “The government is limiting the supply of non-religious schools and increasing the supply of religious ones,” he says. “Either explicitly or unknowingly, they are creating a situation where some students will have to go to these schools regardless of their will.”Some observers are less circumspect about the AKP’s intentions. “Their ultimate aim is controlling society,” says Şafak Pavey, a member of parliament for the main opposition People’s Republican Party (CHP). “In order to prevent a threat to their regime in the future by those who study in modern education, [they desire that] at least 11 out of 40 hours teaching time should be dedicated to compulsory religious education.” As evidence, Pavey points to a leaked audio recording released this summer, allegedly of Erdoğan’s son Bilal – whom, she claims, plays an unofficial role in forming education policy – delivering advice to a meeting of Islamic foundations and local education officials in August 2013. The recording was part of a police investigation into alleged corruption at Türgev, an educational charity on which Bilal Erdoğan serves as an executive board member.

“My concern about imam-hatip schools is that we try to increase their availability,” a voice alleged to be that of Bilal Erdoğan is heard saying. “We are at 10% [of overall pupil numbers], likely soon it will be 15%. Do we want to increase the percentage of available imam-hatips to 25%? Or should we, on the other hand, try to establish a strong structure for the other 85%?” Acknowledging that further increasing the number of imam-hatips may be “unrealistic”, the voice suggests that school administrations could pressure students to take optional religious classes in order to boost Islamic content in normal schools. “If some schools manage to assign 11 hours out of 40 to elective religion classes, that would be like having imam-hatips.” Newsweek could not confirm the authenticity of the recording, and neither Bilal Erdoğan nor Türgev responded to requests for comment.

The audio was likely leaked by police officers sympathetic to the Fethullah Gülen movement, a religious community engaged in a power struggle with AKP, and which has in the past been suspected of smearing its opponents using doctored evidence. Nonetheless, recent developments in education and testimonies from teachers and students in Istanbul partially corroborate the plan outlined in the recording.Official figures from the 2012–13 academic year show that religious classes dominated optional courses taken by students by the final year of middle school. Three of the top four most popular courses for this age group were religious courses, including the most popular: “Life of the Prophet Mohammad”. According to Aydagül, pupils and parents have limited say in which optional courses are available. In September reforms were introduced that give Ankara more direct control over the appointment of head-teachers, who have a strong influence over the selection of available courses. Several thousand were replaced at the start of the current school year, often by imam-hatip-trained teachers, or members of a conservative teacher’s union with close links to the government.

Parents and teachers at several schools in Istanbul say that administrators are already restricting optional classes so pupils are forced to take religious ones. A teacher at one school, which was in the process of being converted into an imam-hatip but still has some classes of ordinary students, said its directors had refused to open several non-religious optional courses despite having the resources to do so. “The two parts of the school are run separate, but the imam-hatip mentality is being forced on the non-imam-hatip students,” says the teacher, who gave his name as “Mehmet” and asked not to be identified. “They are being pressured to take optional classes on the life of Mohammad.”Ayşe Turgut, a parent at Talat Pasha School in Istanbul’s Şişli district, which is in the process of imam-hatip transformation, says that her 12-year-old daughter, who is on the normal curriculum, was teased and called an “atheist” by other students when she asked to be removed from a class on the life of Mohammad that she had been automatically assigned to. “She was very upset by it,” says Turgut.

In many parts of Turkey, however, communities welcome the spread of Islamic schooling. “There’s definitely demand for imam-hatips, because a lot of parents feel there isn’t enough religious education in ordinary schools,” says Mehmet Mustafa Gümüş, 40, who runs a school clothing shop in Istanbul’s conservative Fatih district. “Also, girls and boys are in separate classes, so that’s another positive aspect,” he adds. Himself an imam-hatip graduate, Gümüş believes they give pupils a better education than ordinary schools. “When they have proper religious instruction, they become better people,” he says. “They work harder in all subjects. That’s why we see that many of the most important people in Turkey went to imam-hatips.” Among those Gümüş is referring to is Erdoğan himself – certainly the country’s most famous graduate. At a ceremony for the opening of an imam-hatip in Ankara last month, he heaped praise on the schools. “You will be the main actors in the democratic struggle,” he told assembled parents, teachers, and pupils.Turkey’s leaders have not always smiled on imam-hatips. The schools’ vicissitudes over their seven-decade-long history tell of the state’s complicated relationship to Islam. After Mustafa Kemal Atatürk established the Republic of Turkey on the ruins of the Ottoman empire in 1923, he embarked on one of the most radical state-driven social engineering projects of modern times. Over his 15-year rule, he set about rooting out the influence of Islam over Turkish society. Within his first three years, he banned sharia courts, closed all madrasas, shut down private Islamic orders, and banished religious education from state schools. Most strikingly, he abolished the caliphate – the office of political and religious leader of the Muslim faith that Ottoman sultans had claimed since the 15th century. His reforms aimed to remould the everyday habits of Turks: traditional Islamic forms of headdress such as turbans and the fez were banned, and the hijab was outlawed in public offices. “My people are going to learn the principles of democracy, the dictates of truth and the teachings of science,” he said a few years after taking power. “Superstition must go.”

Since Atatürk’s death in 1938, resistance to his reforms within Turkey’s conservative heartlands has steadily eroded them. His own party – the CHP – opened imam-hatips in 1946 as 10-week vocational training courses for high school graduates intending to enter the clergy. It was meant as a populist measure to win over voters ahead of the country’s first freely-held democratic elections in 1950.

It didn’t work. In what some see as a sign of the unpopularity of Kemalism – Atatürk’s rigidly enforced brand of secularism – the CHP was trounced by the centre-right Democratic party, which won 408 out of 497 seats in the national assembly. Since then, the fortunes of the schools have waxed and waned as Kemalist and populist right-wing governments have come and gone. By 1996, when Turkey’s first Islamist prime minister Necmettin Erbakan came into office, imam-hatips had evolved into a parallel state-funded school system that was educating around 11% of all middle- and high-school pupils – a higher proportion even than today.

When Erbakan was pressured from office by the military the following year, the state cracked down on imam-hatips. All middle schools were closed, and high-school students faced discriminatory penalties that meant they were all but banned from attending Turkish universities – a barrier AKP lifted in 2011.Given this history, many believe ‘positive discrimination’ is justified. “These schools have been subjected to cruel discriminations by the Kemalist military regime for a long time,” says Hilâl Kaplan, a columnist for the pro-AKP newspaper Yeni Şafak. “That is why there are not enough imam-hatip schools to meet demand.”

There are some who contend that the entire Republican project was a mistake that should be rolled back. In a café down the road from Gümüş’ clothing shop, a group of elderly men sit silently watching one of Erdoğan’s frequent televised speeches. “The Republic poisoned our society,” says one of them, 59-year-old Nadir Sezer, a former naval officer, who says he was kicked out of the staunchly secular military in 1995 because of his open piety. “There was a mentality that had been in this country for 1,000 years. What the Republic did was to destroy that mentality.”

In Kadıköy, a staunchly pro-CHP area where the secularist party that Atatürk founded won by a higher margin than anywhere else in the city, people are sceptical. “It’s got nothing to do with demand, it’s to do with forcing the neighbourhood in the direction they want,” says the party’s local chief, Necati Ekşi. A district representative of teachers’ union Eğitim Sen said that in the four schools in the district converted into imam-hatips, many students have had to be brought in from elsewhere due to low demand. Islamic charities often provide free shuttle services to the pupils – a perk rarely enjoyed by ordinary schools. “The imam-hatips are like their biological children,” says Özden Aras, a teacher at Yeşilbahar. “And we are the step-children.”

When Newsweek visited the school, Turkish flags emblazoned with pictures of Atatürk were draped from apartment windows on the surrounding streets, and half a dozen images of him could be seen in the school’s staff room – including a hanging rug woven with his image, and a clock with his face on it. It remains a legal requirement for every classroom in the country – even those in refugee camps set up for displaced Syrians – to include his portrait. Only last year, the government ended the ritual pledge that every schoolchild in the country had to repeat at the start and end of every week since 1933, which included the words: “Oh Great Atatürk! On the path that you have paved I swear to walk incessantly toward the aims that you have set.” Many were pleased to see the back of it – not least the country’s 15 million-strong Kurdish minority, who took issue with lines such as, “How happy is he who calls himself a Turk”.

However, some fear that rather than merely lifting ideological impositions, AKP is slowly moving towards replacing them with its own. “As opposed to secular oppression of Muslims, now it’s the other way around. What was being done to AKP’s supporters is now being done to other sections of society,” says Firat, the former AKP parliamentarian. He fears that the rising social tension caused by the government’s religious agenda could eventually make Turkey vulnerable to a spillover of the civil turmoil currently roiling Iraq and Syria. “Turkey has become so polarised it is literally divided in two, people who support and oppose the AKP, and each side hates the other,” he says. “It’s putting Turkey on a dangerous course.”