Lauren Williams, Al Jazeera

New student allocation system based on exam scores and geography has placed non-religious students in religious schools.

Istanbul, Turkey – Turkish students have begun a new school semester amid controversy over a massive education reform

many say is a harbinger of the direction of “New Turkey” under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

The new semester was marred by a row over a new system allocating students to schools based on geographic proximity and

final exam scores, which saw up to 40,000 students, including non-Muslims, allocated against their will to religious

Imam Hatip-style schools, where Sunni-based religious classes are mandatory.

“I don’t like to mix education and religion, and I think this should be a personal choice,” said Dilek, 40,

after dropping off her 11-year-old daughter at Istanbul’s Profilo Baris Imam Hatip secondary school.

Dilek, who declined to provide her last name, said she preferred not to send her daughter to a religious school but

was left with no choice after her daughter’s technical school was closed and reopened as an Imam Hatip school.

Under the new system, first introduced in February and implemented last month, students are allocated to schools

according to preferences based on their results in nationwide end-of-year exams.

Students select their preference of academic schools, vocational/technical schools and Imam Hatip schools,

which have a compulsory religious component.Those who fail to get into their first choice are placed in schools nearest

to their homes.

But many parents and policy advocates complain the increase in Imam Hatip schools in recent years means non-religious

schooling is no longer available in many areas, leaving parents and students no choice in their style of education.

Opponents complain the reforms were rushed through without adequate resources and consultation, resulting in chaos for

students and parents in an already strained education system.

“The government failed to provide any sound knowledge-based evidence as to why this would be better than the previous

one,” said Batuhan Aydagul, director of the Education Reform Initiative (ERI), a non-governmental think tank at Istanbul’s

Sabanci University.

He said the “complete upheaval” created by the changes had direct consequences of a drop in achievement and an increase

in bullying as students struggled in new environments.

“You can’t implement such a gigantic reform without the necessary resources,” Aydagul said.

Moreover, critics say the new system is ideologically driven, part of a plan by the moderate Islamic ruling AK Party

to “Islamise” education – and they claim forcing students into religious education is a violation of human rights.

They point to the increase in number, and the transformation of some vocational training schools to Imam Hatip schools,

as evidence of this Islamic agenda in the staunchly secular nation.

“Based on the international human rights convention, you have to make sure no one is forced into religious education.”

– Batuhan Aydagul, director of the Education Reform Initiative

Erdogan, who completed three terms as prime minister before being elected president in August, has rallied against the

radical nationalist and secular policies of Kemal Ataturk and derives a large degree of political support from

conservative Muslim voters among Turkey’s Sunni majority. In his successful 2007 campaign, he pledged to roll back

Turkey’s 90-year-old ban on head scarves in public institutions – including schools. Erdogan finally lifted the ban

in 2013 as part of a highly controversial package of reforms.

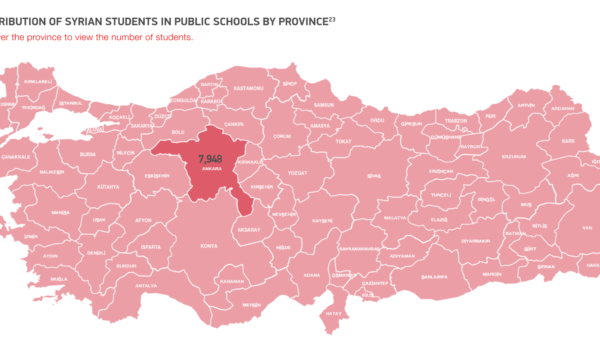

There are currently some 40,000 schools in Turkey. According to data from the ERI, the number of Imam Hatip schools

has increased by more than 83 percent in the last five years, compared to an increase of 57 percent for academic schools

and 23 percent for vocational/technical schools.

According to a 2013 ERI report, more than 1,477 schools have been converted to Imam Hatip schools since 2010.

Turkey’s Ministry of Education, responding to questions via email, said the transfer of schools to the Imam Hatip system

was based on demand.

“New schools have been open and former schools have been converted based on analytics derived from county and provincial

needs surveys,” said a ministry spokesperson.

Aydagul says this is evidence of the ministry’s “favouritism” towards these schools.

“They say it is based due to demand, but if you increase the capacity and supply of these schools, then you are proactively

increasing demand,” Aydagul said.

“Based on the international human rights convention, you have to make sure no one is forced into religious education.”

The Egitim-Sen education union put out a statement earlier this month condemning the government’s lack of consultation

and has staged a series of teacher strikes since September 24 to protest the changes.

The union’s general secretary, Sakine Esenyilmaz, told Al Jazeera the reforms particularly affect Alevis and other

minorities in the country. She referred to a decision last month by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) that found

the Turkish education system violated the “right to education” in a case stemming from Alevi complaints about mandatory

religious classes.

The Alevi complainant took his case to the ECHR in 2011, saying his children were forced to attend classes based

exclusively on a Sunni understanding of Islam.

The court found Turkey’s education system was “inadequately equipped to ensure respect for parents’ convictions”,

and advised Turkey to “remedy the situation without delay” by allowing students to be exempted from religion and

ethics classes “without their parents having to disclose their own religious or philosophical convictions”.

“The ministry has minimised technical schools and turned them into Imam Hatip schools so parents don’t have any choice,”

Esenyilmaz said.

Education Ministry Deputy Undersecretary Muhterem Kurt was quoted in Hurriyet Daily News this month appearing to downplay

the issue, saying only 9,802 students had been affected. Kurt also said parents would have recourse for reallocation from

September. Parents and students have the option to request reallocation in a process reportedly scheduled to

end October 17.

“Due to the high level of students and insufficient classrooms, most of our schools are currently giving half-day classes.

One half of students go during the day, the other half in the afternoon. Our new schools are planned in a manner anticipating four-year student capacity flow,” the ministry spokesperson said.

“It’s been traumatic for everyone. I will look for another school but I don’t know how”.

– Fatima, nurse and mother

Aydagul said that is not good enough, and such change will result in even greater upheaval. “That’s a huge inconvenience,

and daunting for parents,” he said.

Dropping off her daughter at a central Istanbul high school late last month, nurse Fatima, who did not give a last name,

said she will now have to look for another school for her 12-year-old daughter after she was allocated to a religious

school despite their preferences.

“Since the school semester started, we have been so upset. It’s been traumatic for everyone. I will look for another

school but I don’t know how. It is now second semester and I have work. I don’t have time now,” she said.

The power of education to shape and reflect national identity has been acknowledged by both proponents and opponents of

the reforms in Turkey, making for emotional and sometimes fierce public debate.

Commenting in support of the changes in the pro-government Daily Sabah newspaper last month, Adem Ince, a PhD researcher

in education, noted the “educational system of a country gives you many clues about the dominant mentality of that

particular country, as education is always at the centre of governments’ agenda … [and] generally used by states as an

instrument to impose the main philosophy of the state on every single student through compulsory education in order to

strengthen the sense of belonging and create a new generation that is aware of the values of that country”.

According to Namik Havutca, an opposition CHP lawmaker on the parliamentary National Education Commission, the changes

reflect a religious agenda that will negatively impact Turkey’s national identity and international competitiveness.

“The education system changes are made to support the AKP government’s ideology and religious project. The future of the

education system will not include knowledge, science, arts, but dogma and superstition,” he told Al Jazeera.

“How sad it is to say that this system will have no benefits to the future of this country or our children.”