The National, David Lapeska

On a brilliantly sunny afternoon in September, dozens of pre-teens kicked footballs and chased each other across a concrete playground in front of the 60th Year School in Sancaktepe, a working- class district on Istanbul’s Asian side.

Among a group of mothers keeping watch, some had recently protested against the school’s colonisation by a religion-focused middle school, known in Turkey as an imam hatip school. Last year, as a pilot project, the imam hatip school commandeered nine classrooms and welcomed 300 students. This year it has 20 classrooms and 750 students.

The mothers were bothered less by the religious curriculum and taxed classroom space than by a lack of equity: every imam hatip student gets a tablet computer and digital lessons (while the normal middle-school students lug around heavy textbooks); their bus to school is half-price; and their classrooms come decked out with smartboards, projection tools and better laboratory facilities.

“My son sees all this and asks me, ‘Does the state not like me?’” said Nihal Ozturk, who has two sons, one a 13-year-old at 60th Year Middle School. “I’m worried he’s getting a worse education. This new school is telling him and his classmates: the more religious you are, the more the state will love you, the more advantages you will have.”

Marking a dozen years in power this month, Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) has not transformed the famously secular republic founded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk into post-revolutionary Iran or the Afghanistan of the Taliban, as some had feared.

But it has, in recent years, largely remade the nation in its own image, creating a “new Turkey”, as President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and other officials like to call it, where a majoritarian state embraces conservatives, moral codes are prescribed if not strictly enforced and Islam informs policy decisions at home and abroad.

“The goal of Islamists is the Islamisation of society, in thought and practice, and in the standards that people hold themselves to,” Shadi Hamid, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, writes in his 2014 book,Temptations of Power.

Few societies in modern times have been so thoroughly cleansed of religion in such a short time as that of the early Republic of Turkey. In seeking to build a modern, secular state, Atatürk abolished the Ottoman sultanate and ended the caliphate, rubbished the newly created Sharia Council and adopted European legal codes. He fired Islamic judges, forbade the headscarf in government buildings and made Friday, the day of Muslim prayer, a workday.

“He is a weak ruler who needs religion to uphold his government,” Atatürk said a few years after he founded the republic, in 1923. “It is as if he would catch his people in a trap.”

Yet Turkey has never been wholly secular. Rather than sever the links between religion and state, Atatürk handed control of the country’s mosques to a central religious authority, the Diyanet. In so doing, he gave preference to the country’s dominant form of religion, Sunni Islam. Moreover, his reforms largely failed to persuade the masses; the crackdown on Islam sparked a conservative backlash. A tug-of-war between Kemalists, as secular nationalists became known, and conservatives has waxed and waned ever since.

After decades of marginalisation, the more devout have gained the upper hand of late due to a confluence of factors. Millions of Greeks, Armenians and Jews were forced from Turkey from the 1920s through the 1950s, tilting the national demographics towards Muslims. Islamic revivalism gripped the broader region starting in the late 1970s, increasing the religiosity of Muslims from Morocco to Malaysia.

In the 1980s, economic dynamism under the former prime minister Turgut Özal spurred a wave of conservative businessmen from Turkey’s heartland, later called the Anatolian Tigers. Finally, mass rural to urban migration from the 1960s through the 1990s changed the face of Turkey’s cities. These new city folk tend to support conservative parties – such as the Welfare Party of Necmettin Erbakan, Turkey’s first Islamist prime minister – and to have more children than westernised elites, or White Turks.

By the time Erdogan, Abdullah Gül and others founded the AKP in 2001, millions of poor and middle-class conservatives yearned for inclusion. Nine times the party has contested a vote, and nine times it has come out on top. It’s the most dominant political party in Turkey’s history, thanks to Erdogan’s wily charisma, steady economic growth and a moribund opposition, but also because Atatürk may have lost the soul of the republic years ago.

Still, when it came to power in 2002, the AKP enacted a progressive agenda, pursuing greater integration with Europe and expanding individual freedoms and minority and civil rights. This surprised many observers, as whatever he might have said on the stump, politically Erdogan descended from Erbakan, who had strong pro-Islam and anti-western views.

Western officials hailed the Turkish model, but by 2009 the AKP had solidified its hold on power and turned more authoritarian: questionable court cases defanged the secular military establishment; the executive branch snatched some judicial control, leading to the recent dismissal of vast corruption charges; after a harsh crackdown on nationwide protests in mid-2013, Ankara blocked YouTube and Twitter earlier this year and is now preparing a law that boosts its ability to wiretap, search and arrest suspicious characters.

Turkish leaders have been prone to power grabs since the days of Sultan Suleiman, so the shift might be blamed on political culture. But it may also be about the AKP’s grand vision. “Here you have a government that feels the state should be promoting values through the state apparatus,” Hamid said during an interview, referring to the AKP. “You want to consolidate power over the state to promote your agenda. We’re already seeing that – how power is being used to promote a gradual soft Islamisation of society.”

The stated concern is often morality. In October, the culture ministry attempted to cut lines deemed “foul and erotic” from an Istanbul state theatre production of a Goethe play. These lines included, “I want to sleep with you.” The state theatre ultimately cancelled the production. Now a draft law that would establish a cabinet-appointed board to control funding for state-run theatres, ballet and opera, has arts backers worried about future productions.

Last year, Turkey banned advertising and other publicity for alcoholic beverages, as well as their sale after 10pm. Erdogan defended the law as “something that faith orders” – perhaps forgetting that Article 24 of Turkey’s constitution forbids “even partially basing the fundamental, social, economic, political, and legal order of the State on religious tenets”.

Turkey has long been a paternalistic culture, but the AKP’s view of women seems particularly retrograde. In July, Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç spoke of “moral corruption” and warned that women should “not laugh in public”. Erdogan has advised the veteran journalist Amberin Zaman to “know your place”, and urged female college students not to be choosy when taking a partner: “Marry when offered,” he said.

Yet in schools, women have gained a freedom – allowing them to express their commitment to Islam. In September, the government lifted a headscarf ban in secondary schools, allowing girls between 10 and 14 years to cover their hair. The move comes three years after Ankara ended a similar ban for university students (and one year after lifting the ban for public servants), which was one way the secular elite sought to check the progress of conservatives.

Along with women’s hair, education has long been a key battleground. Atatürk closed madrasas and made primary school mandatory, intending to create a nation of secular patriots. Erdogan, meanwhile, has admitted he aims to create a “pious generation”.

“The ideal citizen years ago was one that’s not observant,” Mustafa Akyol, a prominent columnist and author of Islam Without Extremes, said. “Now it’s the exact opposite. If you are someone who drinks alcohol, you’ll have a hard time finding a place for yourself in the AKP universe. They are turning things gradually upside down.”

A 2012 education reform law enabled children between 10 and 14 years to attend imam hatip schools. The schools were initially created to train Turkey’s Islamic clergy, but have since been updated with a semi-modern curriculum and categorised as public schools. A recent law change allows imam hatip graduates to pursue any field of study and become public servants.

Since 2010, the number of imam hatip schools in Turkey has increased by nearly 90 per cent, from 493 to 936. “There’s no way to explain this kind of increase,” said Batuhan Aydagül, the director of Sabancı University’s Education Reform Initiative (ERI), in Istanbul’s Karaköy district. “The result is you almost influence demand by controlling supply.”

The 2012 reform also increased students’ time in mandatory religious classes, which now last nine years, from grade four to grade 12, with more than 95 per cent of the material about Sunni Islam. Technically, parents are entitled to gain an exemption from religion classes. But while requests from Turkey’s few remaining Christians and Jews are generally accepted, requests from Alevis, a heterodox Muslim minority that makes up about 18 per cent of Turkey’s population of 76 million, are usually rejected.

In September, the European Court of Human Rights was unanimous in its decision that that Turkey violates basic education rights by forcing students to attend compulsory classes while failing to ensure respect for parents’ convictions.

The list goes on. The Diyanet intends to transform an Istanbul university into an Islamic academy to rival Egypt’s famed centre of Muslim learning, Al Azhar. Images of human genitalia in some grade 6 textbooks have been replaced with photos of prancing animals. And with classes on Islam recently added to its academies, religious education has crept into Turkey’s bastion of secular nationalism: the military.

“There’s a long game being played here,” Hamid said. “Promoting certain religious values through the education system is important because that’s how you change hearts and minds. Ten, 20 years down the road we’ll see how this plays out in society, with all these students who have gone through a different kind of Islamic schooling.”

The AKP pairs this domestic long game with a neo-Ottoman foreign policy that supports Sunni causes, defends Islam against the imperialist West and seeks to position Turkey as an arbiter of Muslim affairs, potentially displacing Saudi Arabia as the global Sunni leader.

At the Council on Foreign Relations in New York City in September, Erdogan made Turkey’s case. “The Palestinian issue, the problems in Iraq and Syria, Crimea, the Balkans, are all issues that came about after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire,” he said. “Turkey is a country which best knows, understands and analyses its geography, because we share a common history with all the countries and peoples in the region.”

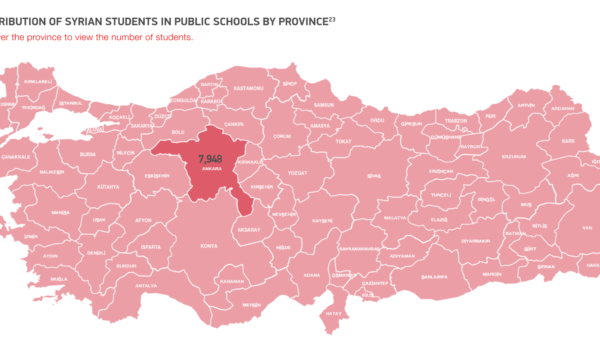

Funding for rebuilding in Somalia, aid to Gaza and taking in outcast members of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood are part of this effort. So is Erdogan’s recent claim that Muslims discovered America, and Ankara’s welcoming of more than 1.5 million Syrian refugees and spending US$4 billion (Dh14.7bn) on their care. Syria is also where Ankara’s Islam-driven agenda has run aground. In 2012, the AKP bet on extremist groups to oust the Syrian president Bashar Al Assad, whom they viewed as massacring his own people.

Turkey allowed thousands of foreign fighters to pass through its territory to Syria and reportedly funnelled weapons and funding to radicals. Cengiz Çandar, a veteran Turkish journalist, has called Turkey’s intelligence agency, MIT, the “midwife” of the jihadist movement in Syria. Many of those jihadists in Syria have now taken up arms with the Islamist terror group ISIL. So, too, have as many as 1,000 Turks, enabling the Syrian conflict to creep across Turkey’s long and porous border.

The battle for Kobani, with ISIL fighting Syrian-Kurdish soldiers tooth and nail for control of a mostly forgotten border city, has transfixed the world. But even since ISIL returned the 46 Turkish hostages it had held for more than 100 days and Turkey’s parliament authorised the use of troops, Ankara has done little to support the Syrian Kurds’ efforts to hold the city.

MIT is reportedly monitoring ISIL cells in Reyhanlı, SanlıUrfa and other Turkish border towns. News stories have detailed ISIL recruitment and fundraising centres in Istanbul, Ankara and other cities. And in October, ISIL operatives shot a Syrian rebel commander in SanlıUrfa during a brazen daylight kidnapping attempt.

“There’s a very clear reluctance on the part of Turkish authorities to move against jihadists,” said Halil Karaveli, a Stockholm-based senior fellow with the Turkey Initiative at Johns Hopkins University’s Central Asia-Caucasus Institute. “If anything I think Turkish complicity, the fact that Turkey tolerates ISIS [ISIL], has become more clear.”

Ankara has taken some action. The government allowed peshmerga fighters from Iraq to pass through Turkey to support their Kurdish brethren in Kobani. Officials have stepped up border and airport security to slow the trickle of foreign fighters and cut the illicit fuel sales that fund jihadist networks. And Turkish police recently raided a likely ISIL safe house in Gaziantep, finding suicide vests and more than 300 pounds of C-4 explosives.

But the AKP’s hands are tied. A more robust crackdown might spark a wave of reprisal attacks. It also has its base to consider. According to a recent poll, more than 37 per cent of AKP supporters either had no opinion on ISIL or saw them as not a terrorist organisation. Many see them as a legitimate protector of Sunni interests in the region – a view often echoed by AKP mouthpieces. In early November, a columnist for the pro-government newspaper Yeni Akit proposed that Turkey establish its own caliphate, reversing its abolishment by Atatürk.

With parliamentary elections coming in June, Erdogan and the AKP can hardly afford to upset this constituency. But perhaps they can’t afford not to. ISIL has made several direct threats against Turkey, and concerns about extremism among Turks have increased more than a third over the past year, according to the Pew Research Center, a United States-based think tank.

“Erdogan and his government have been playing with fire in Turkey and pouring gasoline on the fire in Syria,” said Karaveli, who compares Turkey’s support for jihadists in Syria to Pakistan’s backing of Afghan mujaheddin two decades ago. “It would be very surprising if there wasn’t some sort of blowback.”

Influenced by Sufism, Turkey’s predominant strand of Sunni Islam is relatively pliable and reflects historical links to the West. A recent Pew study found that just 12 per cent of Turks want Sharia law, compared to 84 per cent in Pakistan and 74 per cent in Egypt. Salafism, the fundamentalist ideology of ISIL, has historically been non-existent.

Yet that may be starting to change. Rusen Çakır, a reporter with the newspaper Vatan, recently wrote, “The neo-Salafist movement in Turkey has reached a certain level of organisation.” Akyol said Salafism has gained influence among Turkey’s conservative scholars, and fears the AKP’s ousting of former president Gül, a moderating influence, has altered the party.

Still, he worries more about Turkey turning into Vladimir Putin’s Russia than the Ayatollah’s Iran. “The Islamist core has become more dominant and emboldened and assertive in recent years,” he said. “But they will always be Islamists of the Turkish type – they’ll never be stoning adulterers as part of their legal code.”

The narrative of the undefeated AKP envisions the party running Turkey for the foreseeable future. By the end of his five-year term as president, Erdogan will have been in power 16 years – longer than any leader in Turkey’s history. He recently took up residence at Ak Saray, a 1,000-room palace on the outskirts of Ankara that cost $615 million (Dh2.3 billion) and could pass as a 21st-century version of Istanbul’s Topkapı Palace, from where Ottoman sultans reigned for 400 years.

Many western observers view Islamists as primitives bent on introducing Sharia law and a fundamentalist social order. Yet they run the gamut, much like Marxists. Even in the late 19th century, Islamic modernists, such as Jamaluddin Al Afghani, called for state mechanisms that checked executive power and prevented abuses of law.

In contemporary democracies, the record of Islamists has been mixed. Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood overreached and failed to govern inclusively, while Tunisia’s Ennahda party has shown wisdom and restraint both in and out of power. Turkey’s experience under the increasingly authoritarian AKP suggests an Islamic state, whatever its ultimate shape, can arrive more gradually: floodwaters inching up the wall, rather than a massive wave crashing on the shore.

“There seem to be more mosques, more women wearing headscarves these days, but I can’t say that my private life has changed that much as a result of the state,” said Ozturk, shading her eyes from the sun outside 60th Year Middle School, a bronzed bust of Atatürk gleaming nearby. “It’s something psychological. It’s a feeling, a pressure that’s there every day.”