The New York Times, Ceylan Yeginsu

When Semra dropped off her 13-year-old daughter for the first day of high school, she had to fight back tears as she entered the dimly lit basement classroom, brightened by the red of the girls’ head scarves and the walls emblazoned with Quranic verses written in Arabic script.

Semra had spent years working overtime at her cleaning job, saving enough to pay for extra courses that she hoped would secure a place for her daughter at an academically rigorous secular school. But after taking the admissions test under Turkey’s system for allocating slots in public schools, her daughter was one of nearly 40,000 students automatically assigned to the state-run religious schools.

“It felt like someone had tossed a bucket of boiling water over my head,” Semra said, giving only her first name out of fear that her daughter would be reprimanded at school.

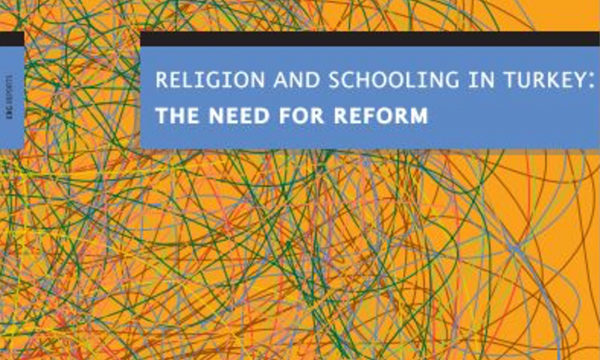

Education has become the latest front in Turkey’s cultural wars, pitting the country’s tradition of secularism against the religious mores of PresidentRecep Tayyip Erdogan and his Islamist allies. The tensions underscore the way Mr. Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party has gradually injected religion into public life over the past 12 years in an effort to reshape Turkish society.

Mr. Erdogan moved slowly at first as prime minister, advocating democratic government, reaching out to the West through the pursuit of membership in the European Union and, along the way, attracting many liberal allies. He was held up as a new type of leader, one from an Islamist background with democratic credentials who could be a reliable partner to the West, including the United States.

But as Mr. Erdogan has expanded his power, removing the military from politics and this year winning election as president, he has moved in a different direction, critics say, cracking down on dissent, intimidating the news media and establishing more control over the judiciary. Along the way, he led moves to restrict alcohol sales and rescind a longstanding ban on head scarves in public institutions.

In the process, his relationships with longtime Western allies, especially the United States, have become strained, not just over his domestic policies but also in the foreign sphere, especially in Syria, where he entered the fight against militants of the Islamic State only grudgingly.

Now, the shift has affected education, as Turkish parents find that, like it or not, the state has assigned their children to religious schools.

Critics and many secular-minded parents say the government has rigged the system by limiting the number of secular schools and building more religious institutions. It is part of an effort, they say, to realize what Mr. Erdogan articulated two years ago as the goal of raising “a pious generation.”

The religious schools — called imam hatip, meaning the one who delivers the Friday sermon — were established in 1923 to train imams. That was after Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey, abolished madrasas as part of a revolutionary plan to transform Turkey into a secular nation-state — and to secure government control over religion. Today, the schools offer modern academic classes, Arabic studies and religious teachings.

Turkey has seen a sharp rise in these schools under the leadership of Mr. Erdogan, himself an imam hatip graduate. At a recent school inauguration, he celebrated the fact that enrollment in the schools had jumped to almost a million from just 63,000 during his 12 years in power.

The minister of education, Nabi Avci, said the increase was a result of demand from religiously conservative families who had been marginalized before Mr. Erdogan came to power.

“These schools were unfairly branded as enemies of the state,” Mr. Erdogan said, referring to a 1997 law that closed all imam hatip middle schools and made it extremely hard for graduates of the schools to enroll in higher education.

“We proved how unfair this treatment was, and now one of them is the president of this country,” he added.

Some critics say that by favoring religious schools, the government is giving them a greater say in overall education policy.

“The imam hatip school community is given more space to contribute to education policy dialogue,” said Batuhan Aydagul, director of the Education Reform Initiative, an independent think tank based in Istanbul. “Their observations, experiences and insights overshadow the needs of the general education system, which is concerning for the overall health of the education sector.”

Mr. Aydagul said that by increasing the number of imam hatip schools, and limiting seats in other schools, the government had left few alternatives.

But Fatih Demirel, a member of the Imam Hatip Alumni Association, said demand for slots in the religious schools was rising. “Parents want their children to be raised in safe environments away from drugs, where they can learn good morals and values,” he said.

Islamists are making inroads in secular schools as well. In September, the government began allowing girls as young as 10 to wear head scarves in classes. Recently, Mr. Erdogan endorsed a call by the government-aligned National Education Council for mandatory Turkish Ottoman language classes — an older form of the national language, written in a type of Arabic script — and classes in “religious values” to be taught to children as young as 6.

“Whether they like it or not, the Ottoman language will be learned and taught in this country,” he said.

Last month, Mr. Erdogan instructed Turkey’s schools to teach children about Islam’s contribution to the arts and sciences, including his own claimthat Muslims discovered the Americas three centuries before Christopher Columbus.

“Our children lack basic skills in core academic subjects and critical thinking, but all the president is concerned about is teaching our children about religion, which they can learn at home,” said Koray Capa, a parent who recently transferred his child from an imam hatip school. “His priorities are warped.”

Parents are also worried that the secular schools their children attend will be transformed into imam hatip schools.

In August, the Yesil Bahar Secondary School in Kadikoy, one of Istanbul’s more liberal districts, was among hundreds of secular schools converted to religious ones. Parents staged protests, and the conversion was reversed.

“They provide free transport and meals for these schools and tell people it’s the same education with a few extra religious classes, so people are easily persuaded,” said Ozden Aras, a teacher at the school who was active in the protests.

Semra spent weeks trying to secure a transfer to a secular school that she said has higher academic standards, sometimes even offering bribes to officials. She was turned away each time because of a lack of vacancies.

“If your child has average grades and you don’t have the means for private school,” she said, “you fall victim to the system and are forced to send your children to vocational schools or religious schools that perform considerably lower than regular schools.”