Perspectives, Aytuğ Şaşmaz

For many of those who work in the area of education policies, it was hard to believe that a draft law entitled “Bill on Amending the Primary Education Law and Other Laws” was submitted to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey on February 21, 2012. In fact, Zaman daily had already published a news story on January 5 about the division of the education system into different stages. However, no one expected the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) to propose a legislation which divides the eight-year primary education into two stages, stage one and stage two, each lasting four years; and allows for distance education and apprenticeship training starting from stage two, i.e. at the age of 10, therefore reducing compulsory education effectively to four years and enabling vocational training to start at the age of 10. This is the same government that has been taking steps since coming to power to increase access to the eight-year compulsory schooling. Submission of the bill to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (GNAT) was merely the beginning of a process full of surprises

First reactions to the bill

The bill was introduced to the media as if “compulsory schooling was increased to 12 years”. In fact, the bill was proposing to leave the authority to increase compulsory education to the discretion of the Council of Ministers and there were no provisions whatsoever related to the conditions upon which this decision could be made. The main purpose of the bill was to disqualify primary education from being an uninterrupted basic education program and to establish schools where different programs could be implemented after the 5th grade. The bill also made it possible to establish secondary schools attached to high schools, therefore students, after finishing the 5th grade, could continue their education in schools that are affiliated with vocational high schools, or imam hatip schools (vocational schools to train Islamic clergy). Distance learning and apprenticeship training were also included in these different programs in the first draft of the bill.

The bill, in general, and the possibility to implement distance learning and apprenticeship training at the primary education stage (for children between 10-13) caused an uproar among the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that have been working for many years on issues related to the schooling of girls and the prevention of child labor. Many organizations, the Education Reform Initiative (ERI) in particular, have issued statements one after another to point out that the bill is far from capable of introducing regulations that will help the advancement of the educational system in Turkey. Upon the reactions, the National Education Committee of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, which met on February 23, 2012 to discuss the bill, decided to set up a sub-committee to rewrite it.

The establishment of a sub-committee and signals coming from the ruling party between 23 and 26 February 2012 were interpreted as if AKP was not going to insist on the bill. The interpretation that the ruling party would step back from the bill became stronger when one of the members of the National Education Committee from AKP and an MP from Mersin, Çiğdem Münevver Ökten, said, “solutions will be produced to remove the concerns” and when the Minister of National Education, Ömer Dinçer, said that vocational education should not be started earlier, but should be postponed to later stages, at a Vocational Education Workshop that took place in Antalya on 24 February.

The rationale of the bill submitted to Parliament was far from satisfactory to many people and organizations. The most important reasons put forward by the government were that the eight-year uninterrupted schooling was a monster created by the 28 February 1997 military memorandum regime, it was harmful for 6 year-olds and 13 year-olds to attend the same school, which was a unique practice never seen anywhere else in the world. According to the NGOs, “eight-year uninterrupted schooling” referred to a system with many examples in the world, which is built on a single education program even though there are elective courses, and which provides children with basic life skills without being diverted to separate programs or vocational education. International surveys have shown that the primary education in Turkey lacked the capacity to give students basic life skills; therefore, as emphasized by the NGOs, it was important to strengthen the primary education and emphasize basic skills to overcome this problem.

Contrary to the statement by Ömer Dinçer, the rationale of the bill was in favor of starting vocational education at an earlier age, as a measure to promote vocational education. While doing so, the text of the rationale defined vocational education as constituting 60 per cent of the secondary education in the EU, whereas data from international organizations showed that only 48 per cent of the students in secondary education were in vocational education programs. Germany was cited as a country that owed its success to an early start of vocational education. However, discussions on the early tracking of children into different types of schools that triggered inequalities were completely ignored and initiatives taken in most of the states of the country to increase the years devoted to basic education were not mentioned. The last point put forward in the rationale of the bill was related to the recommendation issued by the National Education Council in November 2010 to divide the education system into different stages. The recommendation was issued on the last day of the Council meeting without being discussed. Prior to that, the regulations related to the convention and decision making processes of the National Education Council had been amended in May 2010 in a rather hurried way and the proportion of Council members appointed by the Ministry of Education to the total number of members was increased from 60 to 75 per cent.

28 February 2012: 4+4+4 in the halls of Parliament

All that criticism was raised by the majority of the NGO representatives and university deans who attended the meeting of the sub-committee on 28 February. According to attendees, the preparations were not mature to divide the educational system into stages and, even if staging were to happen, it should not be to the detriment of the integrity of the program. They also stated that the eight-year uninterrupted basic education had important benefits that should not be given up, for instance, increase in the schooling rate, extension of basic education, and students’ confrontation with competitive central examinations at a later age. The deputies of the ruling party tried to refute the scientific findings and field observations, pointing out the possible risks of staging primary education, such as possible reduction of the schooling rate for girls, detachment of children with disabilities from school and increase in discipline related problems. They argued that staging the system did not have anything to do with the quality of education. However, the real development happened in the AKP Group. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, embraced the bill to an unexpected degree that was proposed as a political party group bill rather than a government draft, and blamed the NGOs, especially TUSIAD, which were standing against the bill, for protecting the heritage of the 1997 military memorandum.

The draft of the sub-committee removed the possibility of distance learning and apprenticeship training in grades 5 to 8 and took the judgment related to compulsory secondary education back from the Council of Ministers. That was an important achievement. However, the clauses related to the provision of elective courses based on the skills, interests and capabilities of students in grades 5 to 8, as well as the clauses allowing for different programs and types of schools were made even stronger. Another provision was added to the draft, which would make children start primary education one year earlier. The government avoided arguing in detail as to why these regulations were necessary although they were completely in conflict with the previous statements of the Minister of National Education about postponing the age to start vocational training and disseminating pre-school education.

Meanwhile, the opposition parties in Parliament began to make efforts for a more effective opposition against the bill. The first round of the committee discussions was marked by the 12-hour speech of Engin Özkoç, deputy of the Republican People’s Party (CHP). However, the opposition failed to effectively refute the justifications of the bill and to convince different segments of society. When around 100 deputies from AKP wanted to attend the second and last round of meetings, discussions became impossible and probably the fiercest fight in the history of Turkey’s Parliament broke out. The chairman of the committee, Nabi Avcı, had the draft read, voted on and adopted while the fight was still going on and declared that it would be transferred to the General Assembly. That was the conclusion of the committee meetings that left everyone with questions as to whether the rules of Parliament had been followed or not during the committee discussions.

The discussions in the General Assembly were rather uneventful as everyone must have received the message from AKP that the bill would be passed no matter what. NGOs and the opposition lost courage. The bill passed the General Assembly after the addition of several other provisions stipulating that primary education consists of primary school and middle school, each lasting four years; and middle schools can be established together with high schools and as imam hatip middle schools. Another addition was related to the introduction of two elective courses – “Koran” and “The Life of Mohammed, the Prophet”- to the middle school curriculum. Following its adoption by Parliament, the bill was also approved by the President of the Republic and entered into force on 11 April 2012.

Changes in the education system: A batch of uncertainties

The Law 6287, which made history as the “4+4+4” formula, brings forward many changes in the educational system. How these changes will be implemented is still unclear as of May 2nd, 2012, the date this paper was written. One of the main uncertainties lies in the age of starting school. The Ministry of National Education announced that the age of starting primary school is brought forward one year. Previously, children who turned 72 months in the same calendar year as the school year were allowed to start school. Thus, those who were born in 2006 were going to start school in the 2012-2013 school period. The new law however, says that 5 year-olds can start school. There is no regulation as to how the age will be calculated; therefore it is not clear whether turning 5 means turning 60 months or 72 months. If those who turn 60 months are allowed in school, primary schools will have to host almost two times at may students as they normally do. According to teachers, neither they, nor the curriculum, nor the physical conditions at schools are ready for accepting the 60-month-olds. Making children start primary education one year earlier can also have a deep impact on pre-school education, about which great efforts have been made in Turkey in the recent years. Participation in pre-school for five-year-olds (60-72 months) has increased very quickly: two out of every three 5-year-old children were enrolled to a pre-school program. However, this trend may come to a halt when they start to accept five-year -olds in the primary schools. Pre-school education may be overshadowed as the priority of the educational bureaucracy will be to implement the new regulations, and families (just like in the past) may be reluctant to send their 4-year-olds to pre-schools. Turkey may not be able to see the promised benefits of the pre-school education.

How students will be separated in different schools and programs remains unclear. Imam hatip middle schools will be opened for sure. But it is still uncertain whether permission will be granted to open vocational middle schools or middle schools under prestigious high schools. Even slight differentiations between schools may result in the introduction of competitive exams for placement as well as competition among parents and students who believe that the number is too low for good quality high schools and universities. If this happens, students in Turkey will have to pass a central examination at the age of 9. Even though placement will not depend on a central exam, the questions of how to decide which middle school to attend and how to make sure that the socio-economic status of the family will not affect this decision still remain unanswered.

Another fear is the possibility that the transition to middle school at the end of the 4th grade may turn into an excuse to pull disadvantaged children, especially girls and children with disabilities, out of school. In that case, despite the efforts from the central government, schools may not be able to provide a friendly environment for children with disabilities. As the transition to middle school is an important breaking point, children with disabilities may be discouraged to continue school. The same risk is also valid for girls, for whom, even before this law, the schooling rate towards the end of primary education had been dropping despite all the gains of the eight-year compulsory schooling. Research results have also shown that with the eight-year compulsory schooling, there was a significant drop in the phenomena of “child brides” and “teenage mothers”. If the risks in question materialize, this falling trend may reverse and the number of child brides and teenage mothers may increase again.

We still do not know what kind of different programs, schools and elective courses (apart from religious education) will be introduced in middle schools. What we also do not know is whether these courses and school types will be classified as vocational education programs. Uncertainty prevails over other issues, such as whether courses related to religious education will be delivered during or outside of school hours, whether these courses will be “voluntary” or “elective”, how schools will ensure freedom of faith and thought, or how they will guarantee an environment free of discrimination.

4+4+4 and the future of Turkey

The 4+4+4 process draws a very pessimistic picture about the future of Turkey in terms of democracy and the transformation of the education system. Education, an area which interests everyone and which should be constructed on the basis of scientific findings, has witnessed a transformation within one month, which turned the whole system upside down, without any research or impact assessment processes. Opinions of non-governmental organizations and the major universities of the country were substantially ignored. Incidents that have nothing to do with democracy took place under the roof of the Parliament. Unfortunately, it was proven once again that the most important factor to pass a bill is the leader’s ownership.

As we move quickly towards the 2012-2013 education year, the major problem facing the system is the uncertainty of how the amendments will be implemented. Neither public schools nor private ones have any idea or information about which course programs will be taught next year, whether they will serve as a primary or a middle school, how the transition from grade 4 to 5 will happen and, on top of everything else, how the FATIH Project, through which all students will be given tablet computers will be implemented. Beyond all these, the reforms promoting individual development – i.e. strengthening the services provided in basic education according to the needs of the students, postponing and improving vocational education, personal development oriented restructuring of middle school education, freeing the education system from the suppression of central examinations etc – are losing ground. What sticks in our minds is the question of whether it is possible to reflect upon the economic incentive package that was declared only days after the adoption of 4+4+4 by the Parliament, and the statement of “the South-East will become the China of Turkey” separately from the 4+4+4 issue.

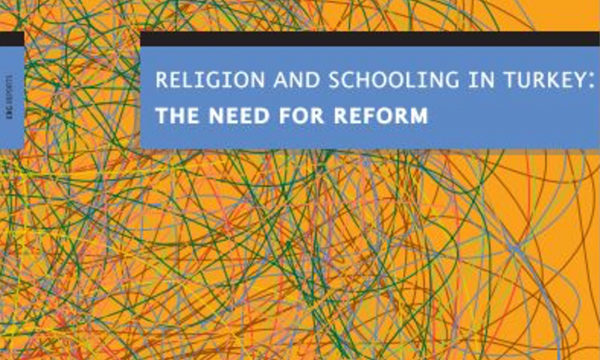

Voluntary courses vs. elective courses:

These are, in fact, two very distinct concepts. ERI, in its publication titled: “Religion and Education in Turkey: Recent Developments and the Transformation Process (2011) defines voluntary courses as follows: “Courses delivered generally outside the school hours which require an extra effort from the student for participation. Here, the student does not select from among different options, but makes an extra request to school management to take this course.” The same publication defines elective courses as follows: “Courses chosen by the student from a set of options and delivered during the normal school hours.” However, the recent law stipulates that the courses related to religious education (“Koran” and “Life of Mohammed, the Prophet”) are “voluntary optional courses”. This provision, of course, reinforces the uncertainties.